In fact, there was a moment in the 2nd half, near the end, when Puyol when to the sideline and said to Pep that he was so tired and could use a substitution. Pep, from the sideline, told him he would hold until the end of the match in a very catalan expression (literally translating to "by my balls you end the match". In catalan doesn't sound so bold, mind you). So Puyol had to endure the last 10 minutes.

|

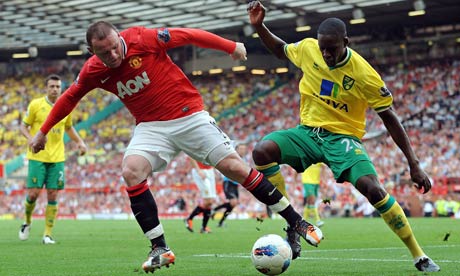

| Norwich impressed at Old Trafford and showed the kind of spirit that is a Premier League selling point. They lost 2-0, however. |

It's the most competitive league in the world. Anybody can beat

anybody on their day. There are no easy games in this league. The mantra

of the Premier League

apologists is well known. Every time a team from the Little Fourteen

(as nobody ever calls them) plays a team from the Big Three (it is just

three now, right?) the cliches come trotting along: in our league nobody

gives anybody anything, everything's a glorious struggle.

It's

nonsense, of course: it's obvious the Premier League is a closed shop

that can be opened only with the application of around a quarter of a

billion pounds. In England in the past decade there have been three

different champions. That's the same as Spain, Italy and Portugal,

poorer than France (four), and Germany and Russia (five). But then in

the past decade there have been Champions League winners from England,

Spain, Italy and Portugal, and not from France, Germany or Russia. It

seems fairly obvious that competitiveness is something that must be

balanced against quality: would fans prefer an exciting domestic league,

or for teams from that league to do well in continental competition?

That's

not to say that a low number of different champions is necessarily a

sign of strength or high quality. In Croatia, Dinamo Zagreb have won the

league for the past six seasons and made next to no impression in

Europe. The problem, Igor Biscan said, is that their players get used to

winning easily; come a tough match, a game against a side of even

slightly lesser ability, in which they have to do things that don't come

naturally, like defending, they have no idea what to do. "Our players

walk through games against villages so they forget how to run," as a

Crvena Zvezda director put it to me a couple of years ago. "But what are

we meant to do? Buy players for the other teams in the league as well?"

Rangers and Celtic have perhaps suffered from that at times in Europe, which may mean that the domination of European football

by Barcelona and Real Madrid many have predicted is not quite so

sustainable as many think. That in turn is something to consider for

those who would tweak the balance of competition in the Premier League

by doing away with collective bargaining for TV rights (quite apart from

asking whether the product will remain so appealing if games are

hideously one-sided). That answer to the Zvezda official's question, in

fact, may end up being "yes", if only indirectly.

If you want a

true range of champions, you need to leave Europe. There have been six

different champions in Japan in the past decade, seven in Brazil. In

Argentina, where the apertura-clausura system

means there have been 20 championships in the past decade, there have

been 11 different winners – but there the spread of champions seems a

function of weakness, with the best players from the best sides being

skimmed off by predators from Europe and Brazil after each championship

in what's effectively a reverse of the draft system in US sports.

But

even if we accept competitiveness per se as a good thing, there are

different types of competitiveness. After all, while there have been

five different champions in the past decade in Germany, Bayern Munich

have won the title five times, the same number as Manchester United,

Barcelona and Internazionale (Porto and Lyon, incidentally, are the most

successful individual clubs in the 10 leagues considered with seven

titles each in the past decade). In effect, in Germany there is a Big

One and, if they fire, nobody else has much of a chance. Whether one

giant and a handful of occasional challengers is preferable to two or

three giants is debatable.

Looking at the number of champions,

though, says little about whether a team at the bottom can beat a team

at the top. To try to come up with a statistical basis for assessing

competitiveness within a league, I looked at four metrics across the 10

leagues (England, Spain, Italy, Germany, France, Portugal, Russia,

Brazil, Argentina and Japan) over the past decade: the average gap from

first to second at the end of the season (how dominant is the

champion?); the average gap from first to fourth (is it only two or

three teams who challenge the champion?); the average gap from first to

last (what's the gulf in quality from top to bottom?); and the average

gap from fourth to fourth-bottom (what's the difference in quality

between the mid-ranking sides?). Because different leagues have

different formats and are different sizes, these gaps have all been

expressed as points-per-game. (Points deductions were ignored).

In terms of exciting title races, it turns out that Russia is

the place to be, with Spain some way back, and the rest trailing far

behind. Perhaps not surprisingly, given Porto's domination, Portugal has

the highest gap from first to second, but what is striking is that

Germany has had the second-least-close title races over the past decade,

a fifth of a point-per-game separating first from second. The gap

between first and fourth in the Bundesliga, though, is the fourth

smallest of the 10 leagues surveyed, the gap from top to bottom the

third smallest and the gap from fourth to fourth-bottom the smallest.

That suggests that the leader often streaks away while the rest remain

relatively tightly bunched.

The biggest gap from first to fourth

is in Portugal. Again, that's in line with expectations: since the

second world war, only Belenenses and Boavista, once each, have

interrupted the flow of titles for Porto, Benfica and Sporting. There is

a very clear historical Big Three who continue to dominate. In Italy,

similarly, the two Milan clubs and Juventus (calciopoli

notwithstanding) have clearly been dominant. What is perhaps unexpected,

though, is that England have the third-biggest average gap from first

to fourth: perhaps the Big Four was always something of a myth.

Brazil

has the smallest gap from first to fourth, which it is tempting to

ascribe to the size of the country. A population of almost 200 million

can perhaps sustain more big clubs that smaller nations. It is also

worth noting, though, the relative immaturity of a national championship

in Brazil; it could be that as the present system becomes more

established, money and success gravitates to a more select few.

But

what's really telling is the last two columns, which show that there is

a bigger gap between top and bottom of the Premier League and between

fourth and fourth bottom in the Premier League than in any of the other

nine leagues under consideration. Far from being the most competitive

league in the world, in fact, it turns out to be the least. The league

where the bottom is closest to the top, rather, is Brazil, which is

remarkable when you consider that the statistics include the 28-team top

flight of 2001 and the slow contraction to 20 in 2006 – the more teams

there are, the wider you would expect that divide to be.

Now of

course an analysis of points tells only part of the story. It may be, in

some hard-to-quantify way, that lower Premier League teams fight harder

before losing to the big guns, and it certainly is true that the

culture of arranged games, mutually beneficial draws and the like, seems

less pronounced in England than elsewhere.

In terms of hard

statistics, though, the message is clear. The Premier League may lead

the way in terms of marketing and self-promotion, but if you want

competitiveness, go to Russia or Brazil.

Next week, I'll look at

how competitiveness has changed in England over time, what the reasons

for those changes may be and what the potential impact of scrapping

collective bargaining for television rights may be.